Publication Date: 05-27-2025

It Comes at Night (2017) review

Dir. Trey Edward Shults

By: Steve Pulaski

Rating: ★★★½

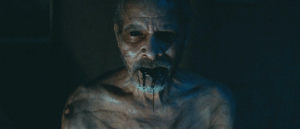

Now this is what I’m talking about. It Comes at Night is a near-masterpiece of form; a supremely engaging horror-drama that’s well-shot, eerie beyond belief, and immaculately paced to boot. Its low-key attributes and sublime aesthetic will have to wrestle with The Belko Experiment‘s graphic portrayal of blunt-force trauma as my favorite horror film of the year.

I’m always weary of these “festival darling” horror films that merit high critical praise from critics who either don’t see or don’t say much about more mainstream offerings that come out during the year, like The Bye Bye Man or The Gallows. In 2015, we had the stylish but mostly harmless It Follows, and in 2016, we had the atmospheric but narratively stagnant The Witch. This year, however, It Comes at Night is upon us and it is as real as a broken leg.

The film revolves around a family that has built a quarantined shelter in the deep woods following an outbreak of a flesh-eating virus. The patriarch of the family is Paul (Joel Edgerton in a performance that confirms his A-list-level talent), a former schoolteacher living with his wife Sarah (Alien: Covenant‘s Carmen Ejogo) and their teenage son Travis (Kelvin Harrison Jr.). The three spend their days collecting water and rationing food, and their nights fearing what they don’t see and only hear. Their safety, however, is momentarily threatened when a man named Will (Christopher Abbott) comes along and tries to break into their home, only to be apprehended and interrogated by Paul.

Will claims to be trying to find water and food for his wife Kim (Riley Keough) and their young son Andrew (Griffin Robert Faulkner). Paul believes the sincerity and the desperation in Will’s eyes enough to pick up both Kim and Andrew and permit them to take shelter in their house. With that, nights are marked by loud noises and unsettling ambience that wakes their family’s dog Stanley and further unsettles an already nervous Travis.

It Comes at Night deals with the feelings of paranoia and dread that compliment desperation and fear all too well. Both families are well-meaning and possess similar motives. The only reason we tend to side with Paul and company is because we saw them first and know a tad more – not much – about their backstory than we do Will and Kim’s. Interposed in the film’s mostly linear structure are a series of nightmarish sequences that frequently show Travis succumbing to the same bloody, ugly fate as his grandfather, who’s body is tossed in a shallow grave and lit on fire during the opening scene of the film.

Writer/director Trey Edward Shults works with cinematographer Drew Daniels to create an atmosphere that’s both smothering and spooky despite its vast openness. The woods is not necessarily a place one would ordinarily deem “claustrophobic,” but Shults and Daniels immerse us so deep in the forest that we hardly even get glimpses of the sky to really know what kind of world or conditions lie beyond us. Most directors and cinematographers would be challenged to shoot in the dark and dimly lit conditions It Comes at Night requires, but the two men work together to assure that even the scenes that are shot in lighting that could adequately be described as being “darker than pitch” are still marked by considerable attentiveness to the viewer’s placement and spatial awareness.

The film really plays like a nightmare of sorts, and complimenting that is the film’s commitment to its emotional heft. Any time one involves family, especially in a horror movie, things become more personal and intimate than if a group of friends venture out some place. Shults’ (Krisha) powerfully executed third act subverts the screenplay into a film that reminds you of the very real consequences paranoia and impulse have, not to mention when they are all cloaked in fear and a fierce loyalty to one’s family and belongings. Marked by a ten second scene towards the end of the film that will ring in the hearts and minds of many long after the credits role, Shults never misses a beat here emotionally, and maybe it’s because horror films tend to negate that part all too often.

This brings me to my final question: is It Comes at Night a horror film? Its humble marketing campaign and trailers would suggest, as would its poster, which could easily be mistaken for another found footage romp. I’m going to go with classifying it as a “horror-drama,” which is what I initially billed it in my mind upon exiting. If you’ve seen Jeff Nichols’ fantastic Take Shelter, you should already be familiar with this kind of film breed, but even then, you might not be ready for how this film manages to wrap you up in its tentacles and terrify you into a situated submission in your seat. This is a thinking person’s horror film and not for those that demand surface-level hallmarks of the genre.

Starring: Joel Edgerton, Christopher Abbott, Carmen Ejogo, Kelvin Harrison Jr., Riley Keough, Griffin Robert Faulkner, and David Pendleton. Directed by: Trey Edward Shults.

About Steve Pulaski

Steve Pulaski has been reviewing movies since 2009 for a barrage of different outlets. He graduated North Central College in 2018 and currently works as an on-air radio personality. He also hosts a weekly movie podcast called "Sleepless with Steve," dedicated to film and the film industry, on his YouTube channel. In addition to writing, he's a die-hard Chicago Bears fan and has two cats, appropriately named Siskel and Ebert!