Publication Date: 01-13-2026

Chan Is Missing (1982) review

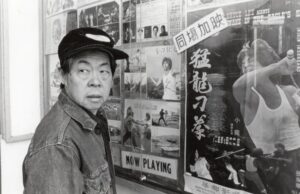

Dir. Wayne Wang

By: Steve Pulaski

Rating: ★★★

To understand Chan Is Missing — the solo directorial debut of Wayne Wang, which went on to be the first Asian-American film to get international distribution — is to at least have surface-level knowledge of two significant things: the fictional character Charlie Chan, who is playfully referenced in the title, and the polyglot nature of Chinese-American culture. The latter is more difficult for non-Asian viewers to assess for obvious reasons.

That said, over the course of 75 minutes, Wang invites us into a neighborhood of colorful characters and dares us to see them through a nonjudgmental lens where all their observations about a singular person are equitable and worthy of attention. As a result, Chan Is Missing not only becomes a character study about a character who is never seen on screen, but a comprehensive drama with light-hearted comedy and mystery thrown into a casual hangout movie.

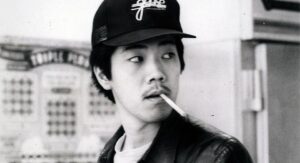

The story mostly revolves around the exploits of an uncle and his nephew in San Francisco’s Chinatown neighborhood. They are Jo (Wood Moy) and the much younger Steve (Marc Hayashi, an amiable and wryly funny personality). As a way to make money and be his own boss, Jo sought to purchase a cab license, but his business partner, Chan Hung, has taken his money and disappeared. Very unlike Chan. Jo and Steve have no idea where Chan might’ve went, so they spend their days traversing up and down the streets of Chinatown, conversing with locals and friends of the missing man, all of whom paint very different portraits of Chan.

Wang’s film is structured in a vignette style, giving us intimate, interpersonal scenes predicated on Jo and Steve talking with their friends in Chinese restaurants, cafes, or their living spaces, and chases many of them with Jo’s narration, which more or less recaps his findings, if any at all.

Steve is under the impression that Chan simply ran off with the money. Jo says that’s unlike his character. Chan’s daughter believes he is a man of principle, while his wife resents him for not making enough money. One of the most fascinating people Jo and Steve probe is a sociology student who tried to help Chan following a contentious encounter with law enforcement. The entire monologue is a breakdown of how Americans can sometimes request simple “yes” or “no” answers to questions, whereas in Chinese culture, there is a pattern of an individual relaying their experiences en route to a response. She talks about how Chan inadvertently drove his taxi through a red light, and the language barrier between the officer and Chan only made the situation more murky. It’s an astute observation about cross-cultural differences, and a showcase of Wang’s insidiously smart writing.

The title is in reference to the fictional Chinese detective character Charlie Chan, created by author Earl Derr Biggers in the 1920s. Chan was one of the first positive portrayals of Chinese men in American popular culture; a direct antithesis to the likes of Fu Manchu and other dehumanizing caricatures. Chan was transported from the page to the screen in over 20 movies, and also existed in various radio serials, TV shows, and comics across multiple decades. Who is Charlie Chan — a character who, while beloved, has drawn criticism from both Chinese and scholarly audiences — and what does he mean to Chinese people? Per usual, it depends on who you ask. Hence why everyone in Chan Is Missing has a radically different portrait of the titular “Chan” painted in your mind. Therein lies the complexity inherent to Wang making a movie about Asian-American identity when there is an absence of consensus amongst the community themselves about what identity should be the defining characteristic.

In doing so, Wang takes us to a lot of different locales in Chinatown; lived-in apartments and Chinese kitchens where the smells of stir fry practically emanates by way of black-and-white-colored fumes through the screen. Wang’s film takes us where few, if any, accessible American films have ever taken us before. Often times, American audiences believe they need to be dazzled by plunging deep underwater or beyond planet Earth in order to be dazzled. Chan Is Missing simply takes us to a neighborhood we’ve never been, and it’s about as enthralling as any movie I’ve watched over the last few months.

It also says something about a movie in which the opening minutes contextualize a mystery that, in the end, remains unsolved. There’s a plot-wrinkle involving a “flag-waving incident” centered around supports of mainland China that provides some context, but nothing definitive. “It’s not the destination, it’s the journey,” is a cliché in life for a reason; it applies here. Wayne Wang’s boundary-breaking debut set the stage not only for his own directorial career, but also Justin Lin, who would take flight with his own stupendous debut in Better Luck Tomorrow and get handed the figurative and literal keys to the diverse Fast and Furious franchise from films three through nine. There’s an argument to be made that Wang was on the DIY-filmmaking trend even well before the likes of Spike Lee, Richard Linklater, Jim Jarmusch, and Kevin Smith. That’s a lot of legacy to put on a black-and-white film with a $22,000 budget, but few, so-called small-scale efforts are remotely capable of producing such a ripple effect.

My review of Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart

My review of Slam Dance

My review of Eat a Bowl of Tea

My review of Life Is Cheap… But Toilet Paper Is Expensive

My review of The Joy Luck Club

My review of Smoke (1995)

My review of Blue in the Face

My review of Chinese Box

Starring: Wood Moy, Marc Hayashi, Laureen Chew, Peter Wang, and Presco Tabios. Directed by: Wayne Wang.

About Steve Pulaski

Steve Pulaski has been reviewing movies since 2009 for a barrage of different outlets. He graduated North Central College in 2018 and currently works as an on-air radio personality. He also hosts a weekly movie podcast called "Sleepless with Steve," dedicated to film and the film industry, on his YouTube channel. In addition to writing, he's a die-hard Chicago Bears fan and has two cats, appropriately named Siskel and Ebert!